Introduction

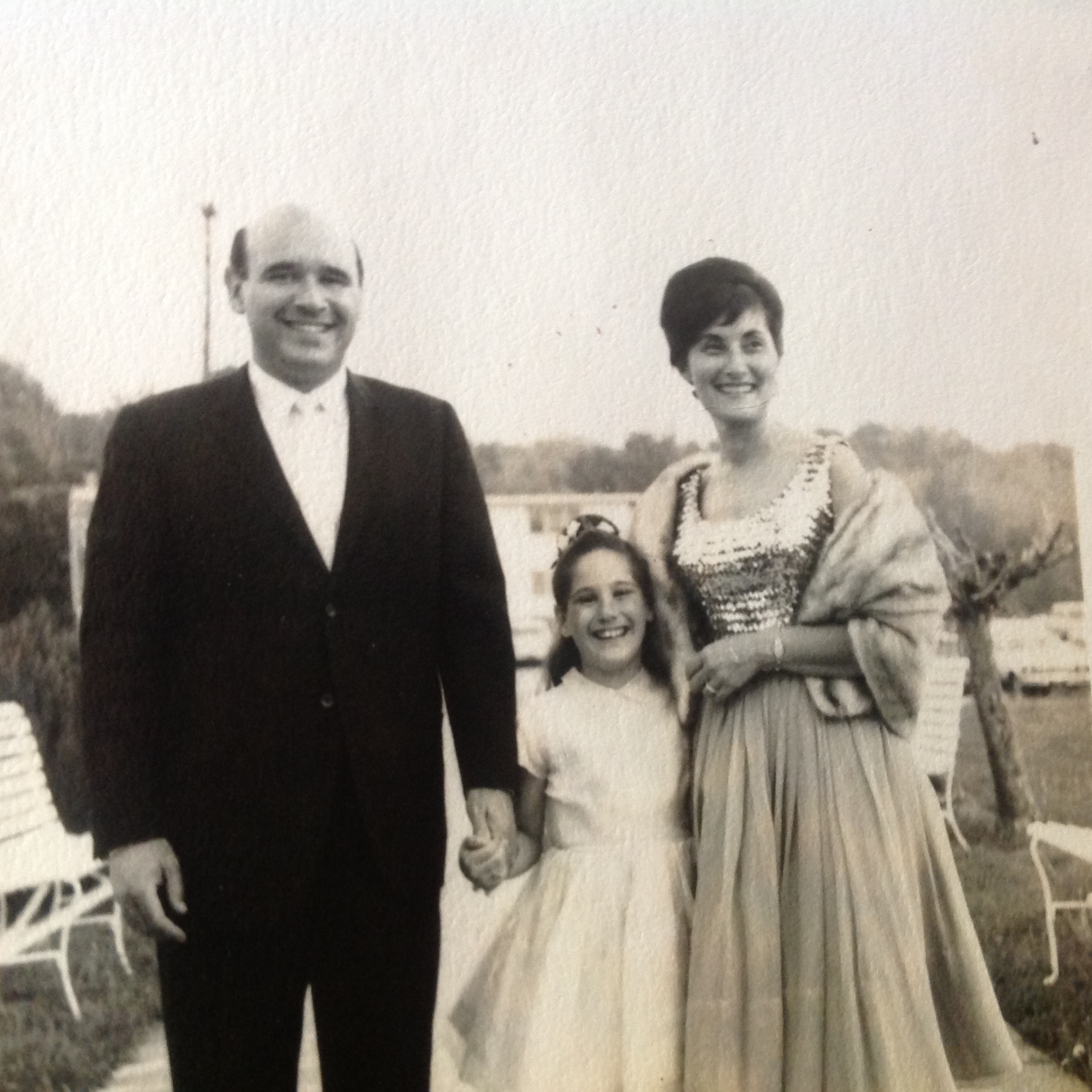

Seventeen years before their deaths i became my parents’ power of attorney. And then in 2014, broke, indebted, and enfolded in a blur of dementia, I brought them with me to live in the town down the canyon, where I could see them everyday. In their wheelchairs, diapers, psych meds, they lived for another few months. When they died, I buried them on my land. This was the hardest, and most triumphant accomplishment of my life.

Here are some selections of a memoir-in-progress, the last years of our time together It’s entitled Strands of the Rope, which is the translation of Chezar.

What Shall We Do?

July 2014

How to begin? What first chapter do i want to tell you about my the three of us? Our name, Chezar, means ‘strands of the rope’, a second or third cousin of my dad’s told me. I give a tug from my own last, fraying strand. Nothing tugs back. It’s been seven years since they died. How will I ever de-strand? How is my identity tied to them, besides this bonded, filial, three-way trip-hammer heart?

A parent can be a mirror, a fencing foil, a sheltering tent, a prophesy. I’m an only-child—so, what have I been? I’m an only child, and the three of us lived, enmeshed and on top of each other for 18 years, sewn together but separate. We lived together in our separate columns of branching bubbles with such diverging realities. It’s like that opthamolgist’s machine with all the lenses to choose from. And there we are on our tight line of three chairs choosing lenses.

I’m an only child, now an adult orphan, for life. No witnesses to my childhood left, and only unreliable witnesses, ever. How accurate is my child’s memory? What did i make up? What do I think I remember? How much of memory comes from photos, or stories adults told that I memorized as fact? My parents did not always tell the truth. I grew up in a house of secrets. I’ve read that a family of secrets births a detective. Who were these people?

I play a game: three words to describe your parents’ personalities. My mother’s—Kind. Willing. Haunted. My dad’s—Fun. Sweet. Angry. Both were seductive. Both were great story-tellers, and very funny. Both were devious, controling, and secretive. Me, I’m prone to confessional over-sharing. I’m still trying to build an army of witnesses. This need of mine for connection is so old that every circuit of possible kinship begins to smoke, threatening combustion.

My mother’s secrets were sourced from shame and denial. My father’s from pure deception as a natural con-artist. She loved with an industrial-strength doting; her nervous habit was a heavy hovering. As if she only had us to keep her upright and alive. Daddy and I were her whole world. Her tiny family defined her. Maybe this is the way with mothers and wives. I wouldn’t know. But here’s where she stood out from my friends’ mothers—she didn’t drive. She didn’t work outside the small apartment. When we left each day, she cooked and cleaned, walked to and from the store—ten city streets away, her arms full of shopping bags, and she waited for us to come home. Having abandoned her own self for ours’, she’d strip-mine us for stories of our days that neither of us wanted to share.

I was a wild child, even as a baby, rebellious and too smart for my own good, as she’d say. I lived inside the bouncing hole at the heart of a whirlpool of undiagnosed A.D.H.D., and was generally out of control. Not knowing what else to do with me, Mama took me, daily, in my stroller and later by the hand, to The Bronx Zoo. It was a nice walk, just across The Bronx River Parkway and Fordham Road, and I was calm there, enthralled by the animals. It set me up for a lifetime of preferring non-humans to people.

I was overwhelmed by her attention, the smothering gave way to mean-

spirited consequences—habitually slamming doors, roaring “Leave me alone!”—As a teen, my life was governed by scams to escape that cage. Early on I was deeply into drugs, into sex—anything that could lead to temporary transcendance from the bonds of being held that tightly. My whole life, I realized much later in therapy, was about not being Her. She would pull me close and tell me, for as long as I would hold still, “Nobody will ever love you as much as I do.” It was a spell she draped over my life, unknowingly. A curse and a prophesy, as when she would say, furious with my wild behavior, “You should have a child like YOU!” And so, no children for me, and no great love. Fulfilling the spell she’d cast. I never wanted to be loved that fiercely, that totally ever again.

She was a great storyteller, and could be very funny, but mostly what I knew of my mother’s identity was that she was a love artist. I used to say she had enough love in her for 15 kids, for a tribe of children and grandchildren who might love her back better than I could. And yet, I am the closest thing, the only chance she had of leaving something of herself behind. I’m not young or a mother, not immortal, but I remain.

She was a Pisces, this love artist, and a deeply emotional woman. She’d worshipped her mother, who never gave her much love back, and was haunted for her life by the secrets of incest perpetrated by her alcoholic father. I called her Mama and she called me Mama. I never met my grandmother, and wish I could say the same for her husband, who fucked with me too, until i told Mama, and she never left me alone in a room with him again. “He’s sick”, she would excuse him, “He did that to all your girl cousins.” She unwillingly enabled him always, and nobody talked about it, ever. She never said what he’d done to her. She just forgot it in a crippling disociation that resulted in O.C.D. and a constant fear of men, the nighttime, anything out of her control. It was only in therapy, at the age of 76, that she remembered, but didn’t name my grandfather. Not to me or anyone. She’d learned to keep secrets in this way.

It wasn’t a household of books or paintings. Neither of them went to college. She could have been a brain-surgeon, a judge, a professor—she was that smart. But she held herself back, for his sake, and raised me with the warning that I should never be smarter than my boyfriends or my husband. The culture that surrounded me growing up was popular cuture of the 50’s—so bland, but for the exception of Mama’s strict religion. She was a traditional Jewish woman, bordering on Orthodox, and her practices were unquestioned. She lit candles every Friday night, consulting synagogue calenders for the exact time of sunset, every week. She kept Kosher, fasted fastidiously for the high holidays. This and shopping for used antiques and bargain clothes was her culture.

For his culture, my dad preferred Sinatra, handball, and infidelity. He was like a member of the Rat Pack—dressed like them, talked like them, was a womanizer like them—he wouldda fit right in. Mama knew about his cheating, had him followed, checked his pockets, interrogated him mercilessly. I heard it all—she told me everything when i was way too young to deal with it, and I never forgave him for making her so miserable, so nervous and heart-broken, confused and a little crazy. He was a player, and she was a virgin. He was the only man she’d ever had sex with; she never had an orgasm in her life and she told me that too.

Other than blaming him for all that she suffered as his wife, I completely adored him. All the kids did. I used to think of him as the Pied Piper, and I was jealous of the attention he gave to my cousins, and then their kids, to his friends’ kids, and to my friends. He owned the room, a natural comedian who made everyone laugh. And he was my best buddy for years. My dad was a handball champ at the 92nd Street Y in Manhattan, and he played every weekend in The Bronx, at Shorehaven. Crowds would gather to watch him slam that ball; as my mama sunned herself, gorgeous and covered in oil on a lounge chair, he hit the hard, fast, tiny black ball with his gloved hand. He ran and sweated and killed it. A champion.

And I always imagined that he wanted a son—but all he had was me, and so he taught me all his favorite sports—sledding, skating and bike riding, swimming, diving, and hitting balls, hard. When I was only six years old, I was infected with horse fever, which would last for decades. We lived in an urban wasteland, but he searched out and found all these weird little stables in Queens and in Brooklyn. He would drive me to one or another every weekend, wait and watch while I learned how to ride.

And now, most of what I remember was the years of their end. How she stood, hair blowing in the tropical breeze, eyes on the parking lot, waiting for me, every time, until she could no longer stand. There she, grinning on is on the third floor catwalk of their Florida condo as the shuttle pulled in. How she wanted to feed me as soon as I walked inside. How she stood in the same spot again, accompanying me as far as she could when the shuttle returned to pick me up for the airport in Ft. Lauderdale. How I’d cry for the whole drive, quietly. And on the plane too, as the green landscape of the American Tropics became the dun fields of the midwest and then Colorado. How he waited for me too, smiling dressed in the clothes she’d lay out for him.

And later, for the last two or three years, when they lived horizontal, beside each other in bed, all day and all night. I would let myself in then, and how she still smiled with her whole beautiful face when she saw me. “God bless you, Sweetheart” was their greeting to me when i arrived and when I left them. How we all cried. How she would tell me, over and over again—“You’re my favorite person in the whold world, and you always have been.” For years I went there for one week every month, fuelled by a complex swirl of obligation, guilt, and love that still overtakes me with tears, even now when they’ve been gone for seven years and every cell in my body’s been replaced by a new one.

Strange that caregiving means the same as caretaking. And that both are just forms of control. Being their caregiver, or whatever I am, feels like being burned at the stake with wet wood. What can I control—I can make a cup of tea. I can open and shut windows. I can fetch water for the beloved garden. Oh, to think about sinking into a garden where I could drop this heavy burden of seeds, at last.

Modern people live too long on hanging bridges, swung way out over vast regions of time, strung out on pain, meds, and promises from the medical-industrial-complex that death is just a failure of medicine. All trying to die as slowly as possible.

I was in charge of my elderly parents’ deaths. I never wanted to be in this position, responsible for another human life. Making such intimate, urgent decisions. What do I want for them? Only that asteroid—oh, the asteroid! I dream of it!

Asteroid, blazing out of heaven, glittering blue and crimson. You out there in the darkness orbiting, rolling those cosmic dice. I call you to come—in the dream I am Mistress of Asteroids. Send them off on their missions to Republican Party Headquarters, Exxon, Monsanto, the Pentagon. 351 Keswick C, Century Village, Florida. Here are the coordinates. Go gently. Go strongly. They'll never see you coming. There are my parents, in their beds, breathing deeply, sleep sprinkled, softening and mumbling, surrounded by photos of dead people, and me. Holy asteroid, you decide, hovering briefly over the golf course, shooting sizzling sparklers. See them there, 3rd floor, terrace with the metal slats. Consider this target. Go! The sudden flash, a compassionate, quick ending, together.

If only we were born in test tubes, it would be so much simpler. No struggles with individuation, neurosis, guilt. Nothing inherited but breath. Just put me in a clean silver and white room, on a high shelf in my petri dish. No inheritance of trauma, no ticking danger of minefields hidden in my soul. No hovering Other to hold my ankles as I make for the door. Or the spout. Born in a test tube. An efficient, simple delivery system. Families?—Why? If only we had instincts and strength enough to be born and crawl away clean. If only there wasn't this trap, these chains called family, obligation, culture. The only culture would be what's lining the petri dish. Like yogurt. One meal and slide on out of there, creamy, yummy, and bye-bye. Moving on cleanly to the life that is mine and mine alone.

Florida

Breathing—

Once upon a time, there was a space

not warm, not safe

and a kite that had chewed thru its string

to run wild among the stars

and sometimes she wrote it down

but mostly things happened and she forgot them

because life was enormous

it was endlessly windy

and there was no tether

and she dreamed of rooted things

of being saved

tied down with heavy stakes

or sprouting wings

to fly home to peace.

Once upon a time

there was a weird paradise called Florida

and in her mother's house things can be so soft and lulling

the bedding, her mothers’ skin, the way time flows

but its’ a trick

she learns to duck and cover from the jagged edges

and so misses the authentic softness

when it comes

when it comes, she is not there

she is a suit of armor

a sort of anchor

a red light flashing in

and out of consciousness

she hasn't breathed for days.

My dear ancient fierce terrified demented parents, condemned to a nursing home, by my own hand. It's fucking Shakespearian. I live up here on this mountain without plumbing. They can’t join me here. And how i plot their daily lives, their daily deaths, trying to smooth all complications, to fix them, when it is what it is. Therapist says Today is Wednesday. My mother is dying. Both these are true. Just love. Just love. Pokin' around in a hole that doesn't really need fixin', because, there's nothing wrong here. Nothing wrong. Just gotta be strong enough to stand it.

I know I’ve swallowed the hook, caught in the exhausting emotional realms, and a tangled net that keeps me so on the edge of all things. I leave it to metaphor, and to superlatives—the drop so sheer, the fall so steep on the so-sharp stones. I want to stop being a drama queen. I am the daughter of a high-drama queen. Maybe i can be demoted to drama countess or dowager drama countess.

Mama calls her husband lazy. He was, for their whole lives, but now he’s just demented. Stopped taking care of business when he retired at 66. Well, but really she is the one who paid the bills, took care of all the paperwork,all the bank balances and all their little shitty investments. He just made the money and signed everything. Him with all his big shot connections, his rich pals with all the answers—he never made a good financial plan, never got great advice from anyone about the future. And then, he just disengaged at fucking 66! She did what she could until she couldn't anymore, and then haunted by insomniac nightmares of debt she too—depressed and despairing, broken hearted and shrunken minded, retired from the world and the work of her life. And life shrunk.

The neighbour, Annie says, "I feel so sorry for them. They don't talk to nobody. Nobody talks to them."

Annie's one of those energetic Italian New York women, who, like the energetic Jewish NY women, like to worry. Who take it on. She thinks I should write to their Republican Senator—about the insurance that wouldn’t pay for the hurricane damage and how they were forced to take a 2nd mortgage on their paid-of apartment. So now they have no equity and a huge mortgage, and their long-term insurance plan, which paid for aides for five years, will end in 6 weeks and the aides will then cost $11,000 a month. There’s no way to do this.

"It's a disgrace, these old people, how they get taken advantage of!" Annie says they call her Tornado cos she's such an action figure. I love her—she's a little crazy but it’s good.

Fishing for future intel, I spoke to a realtor. We met in Annie’s apartment, hiding it from my parents. It’s September. He says do it and do it now; He says this building is the most valuable of the hundreds here, yada yad. This is the season, right now to put it on the market. Maybe sell it by winter. So this is possible, my plan is becoming more real. Maybe that’s why they call this guy a realtor. Bada-boom.

I’ll be home in four days. The days are weird beads that grow teeth when i try and domesticate them to a simple string, a necklace of solace. Simply strung along, i am the bead in the center, the only one not demented. I hold all the cards, the string, the beads, the phone, the magical numbers to ineffectual strangers who slide me complex mixed messages all day, down long-distance strings on a terrible phone connection.

Late at night in Florida, I stand over their sleeping, soft geezer bodies. All curled up like pieces of letters, bits of broken sentences. Tuned and spooning at a great distance in their separate dreams. Reminiscent of pods, drifting in time— she is the pea and he's a beat up old chili pepper. Their sleep-curved forms in the ghost light. Their twinned breath turns, twining these walls, remembering better days. Still, they are happy, often. They are in love in a simpled-down peace. They are pared back, they are paired up, and I, the singularity watching them sleep, feel a little jealous. I always have. This kind of love, the long-time belovedness of my fantasies blooms here, in this warm soft bedroom that's not mine, where I can glide in, lie down gently next to her soft curved form and let my quiet tears fall into a still-damp pillow.

Here we are. Here where she embraces me in her frail soft fierceness.

“You're mine! Nobody can take us apart.”

She begs me, childlike, to stay with her, and I say

“Come to Colorado. We can be together forever in Colorado.”

Just love. Just love….

Early morning. I go in and there's the Haitian aide bending over Mama. Iveny says she has passed out. Has the blood pressure machine on as she wakes, pale, soft her face an apple doll. Ivenny is pulling her up—Drink juice, Mama—we pull her up on the bed. Oblivious, he lies beside her, his back to her. She points towards him, croaks out, ‘One day they'll tell him I'm dead and he'll say Who?’ He asks me how she feels. ‘Turn over and look at her I say. Ask her.’ He sighs. His sighs sound like "Wow", sometimes "Pow", puffs of air, such a big struggle emits from him, but always he says he has no pain and nothing's wrong. "WOW!" he pulls himself up on his left side. I put in her hearing aide and she starts to lie. "Nothing’s wrong. I'm fine." She's crying, softly. The fan turns slowly overhead. The day turns to mush in the front of my skull. The sign that I wrote myself last night is propped up on the tea kettle reading "Go to the Beach" drifts under fresh waves of the fan.

The lawyer, the doctors, the insurance company, the home health care agency, the Jewish Services social worker, the Catholic Hospice, the bankers, the accountant, the FedX driver, the FAX machine. The glittering ocean, rising and sliding home. Who could we three be if everything truly was Perfect? I ask the sea, and all she says is "SSHHHHH. SSHHHHH." Cos probably we both have better things to do than drown in these questions on this perfect day.

My brain is an open vein that pours out bloody stories. This is my life, beaded by planes and countdown days, tugged here like the sea, yanked, dizzy with force, insisting against my muscular struggle to mark out one fixed place, and stay there, making a life that’s my own. Here we are. Pay attention. Clear salt waves and churn of sand. Here, wanting buoyancy.

Here, trespassing on this hotel beach chair, waiting to be evicted by the scruff of my skinny neck, by the collar of my wizened life, I'm a tough old thing, but there is so much more tough ahead. I grow more muscles, while she faints upon waking. I say Mama, what if this is just a doorway through to something like perfect bliss? What if you fearlessly step through that door to be free of pain and anxiety. Just be a bead on a salted string. Just forgive the future, and forget to worry about the past— just slide it away like that bead on abacus. The string is strong and can hold everything, Just be NOWNESS and I will too, without stabbing pitchforks to poke you all sleepless night long, without longing because you have ARRIVED. What if i believed that myself?

At the Pool. Here we are. I walk to the edge of glistening turquoise, tighten my toes, and dive into space and then the soothing wetness. The water is so holy! So holding. How did I not know this? And I swim, flip, back-kick, burst to the surface and burst into tears. I pull my shoulders up at the deep end, hang there sobbing. No one is here. I can cry. Pools are great to cry in! Also I didn't know this. You can wipe your sobbing face off, you can flip upside down for a good rinse, you can scream underwater silently, watching the bubble, and you can blow your nose clean too. The blue of this tropical sky is a perfect crayon. The palm fronds are lit, kissed with some electric charge and drooping like huge feather dusters. My mother and father are dying in Paradise—there's a memoir title.

In the middle of the sleepless night, I check on Mama and she's not in bed. Squinting through the gloom, I see her on her hands and knees, crawling over Daddy. I wake her, not easy without her hearing aide.

“Mama, go back to your side! MAMA!”

“But there's all those other people!” she insists.

I get her settled while she complains about all the others in her bed, kiss her goodnight, go back to my mat on the floor, and restlessly check on her in a little while, and she's gone again. I find her in the bathroom, rubbing the hell out of her eyes with the terrible tap water. She has cancer on her eyelid, her eyes so swollen. I lay her down, find her eyedrops, find ice and washcloths, then I lay with her for an hour while she thrashes, trying to rub them.

I imagine the ‘other peope’ crowding her in her bed, swarms of ancestors, never-known beloveds cuddling close, not helping me hold her here, but welcoming her over. Here we are. This portal. This parallel world. This gentle hiss of green trees on that golf course, netted with happy hunting dragonflies, where I walk twice a day to feed myself to the mosquitoes. Sacrifice for what you hold to be Sacred. This emerald flowing fountain of gleeful hibiscus, ficus, banyon and rubber trees that shimmies every bit of love towards me, right now, being here.

“It's not fair!” she groans, so sad and exhausted and in the bed at last, but not sleeping. She never sleeps anymore.

“She’s in bed 18 hours a day”, I'd told Ira, the visiting rabbi.

She is indignant. Doesn't want it to be true. It doesn't seem true.

“And she has no one to talk to here”. I tell him, “She’s depressed and lonely and tells me she goes to bed for the day cos there's nothing else to do, no one to talk to.”

Iveny glares at me.

“Nope, Mama, it's not fair.”

She adds—“And no one to help us out financially. What happened to The U.S. of A.? Where are they? I thought they were supposed to...to..."

and her imagined nation-as-savior patriotism hangs there a moment in the chill of the air-conditioning.

“No Mama, they don't help anyone anymore. Just corporations and millionaires.”

“Well, who's going to take care of YOU?” She asks me.

“Nobody Ma. It is so totally not fair!”

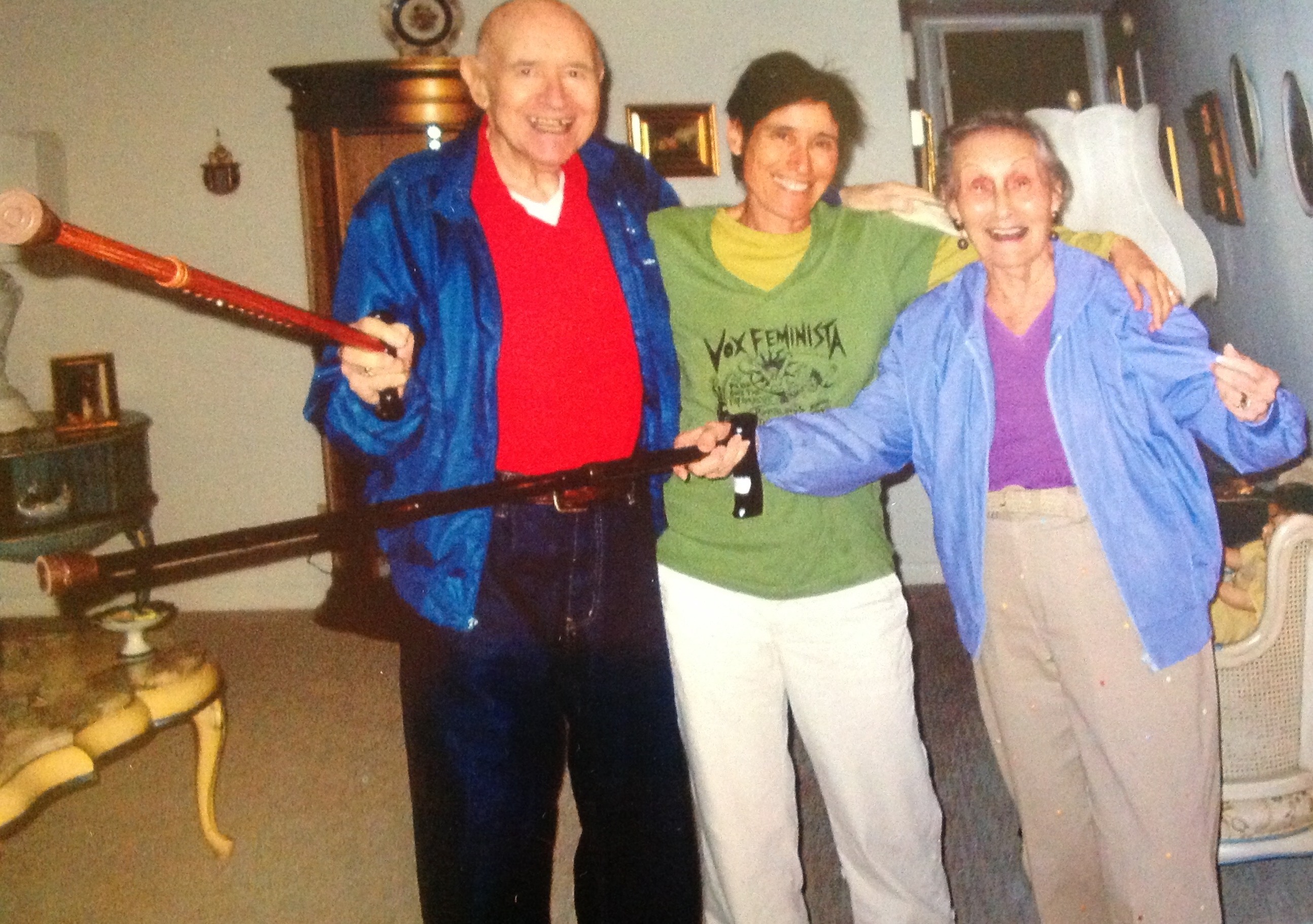

Mama, clowning on the catwalk, Florida 2013

Laughing at dementia, her last year, Florida 2013

Here We ArE

Late July

“Worry is a way to pretend that you have knowledge or control over what you don't. Worrying is meditating on shit.”

Florida

In the Land of the Lost Chezars, it's crazy time. I try to remember that this whole trip is about love, and that it's a pleasure and a privilege to serve my parents. Washing their laundry, cutting their rnails, cooking them dinner, solving small problems. Tossing out bills when they’re not looking—save her some stress, why not? This is love.

I told told them, first thing in the door that I’m taking them to Colorado with me, and how and why—I tell them everything, watch her wanting to argue immediately—

“It's not Fair!”

And then she sort of relaxes back and curls into the chair, like a drug hit her and I keep talking until she and Shelley are both fast asleep sitting up in their kitchen chairs. Afterwards, we cuddle, and I bring my big red stuffed dog, 'Girlfriend', and Mama says in a three way cuddle with me and the stuffie, “Get me one of these.”

“Sure, Mama.”

And she says “I'll take it on the plane with me to your goyishe homeland”.

So she WAS tracking me earlier! Maybe this will work after all. I vacillate but less and less, spend more time acting as though I believe this huge shift move is possible. I go into the other room, lie down on the floor to sleep. The smell of urine softly smothers my thoughts. I will bring them home to Colorado, to the love. I will stop leaking energy, go forward only.

Shabbas. Candles she can no longer light. I hold her small, trembling hand in mine and light them. She prays, looking like she always looks praying over the shabbas candels—face covered with her hands, her whole body rocking. She rocks so far out, she alwasy has, but i go to stand behind her just in case. She's so agitated tonight. Officially out of her mind.

Lying with Mama in bed. Maybe I can just cuddle like this, wordlessly for the next nine days. A pleasure, I repeat, a privilege. Try to sleep.

Nights in Florida are like this—I, watcher in the phantom light, sleepless night listener. I squeeze into the softness to stroke her calm, press all this love into every crevice. I would rather breathe her sleepless exhalations than lie on the floor alone under that incessant slow ivory blade. Out of her mind, but so sweet; totally deaf and it's funny. You can't argue with her or tell her anything—she's standing backwards, lost in the closet, stuck facing the wall in the dark, she's putting on 5 pairs of panties, she's turning all the switches on and off, leaving the water running in two rooms at once, talking so loud to Daddy, but she can't hear that he says he hears her. Just love.

5:20 a.m. Just love, and Indica cannibis flowers, inhaled deeply. And my List of Lasts grows longer. No more candle-lighting starts the tears flowing. No more freedom for them, their stolen soverignty. The nursing home is arranged; they can’t live with me. I have no plumbing, and the altitude is way too high. I hate the idea of a nursing home, but they need the support. They’ll never live alone again. I’m nostalgic already for ficus, banyon, rubber trees. The great cosmic hand starts to wave goodbye. Palm out, painted in groovy symbols—cosmic irony. A slow hypnosis.

There are so many ways this could go. So many bad, bad ways. Lying next to Mama, her 20th hour of sleep, spooning her tiny butt. I’m crying softly onto the pillow. Just love, I pray. Say aloud to no one awake, Here we are. July 20th, 2014. The beginning of the end. One more bump on the trail to eternity. Where are we again? It’s contagious, I too am losing my mind. What to do? Go out in the moonlight to the deserted golf course. This one banyon tree reminds me of us, connected and dropping her roots like wishes, like plans from the sky to the earth. Walking so slowly, on. Twined by shaky lacy vines that swoop and struggle upward to the tippy top, then wave, blind and nimble as a pea vine to find the next thing. I feel like that. I stand still underneath the tree, one finger extended, wanting touch—to be taken up there into the canopy of calm green, trembling.

I need something to help me relax. Mama has so many pills, and all the bottles look alike. I tear through the medicine cabinet wanting a sedative—playing endocrine roulette.

Remember this, through the soothing drugs and the jagged trauma. The fall of sheer creamy drapes, hypnotic pulse of the big ceiling fan, the mama's breath, death scented, how she could not speak, her eloquent nods nodding off. How sweet the needle in my heart pierces. How I wet her pillow nightly with warm salt tears. How I cannot stop crying, like a faucet she would say if she could say anything.

To wake this sad, one more morning in a row of them, to the sorrowful, stunned heat. July in Florida. Oh, remember this—the problems compiling conspire to piles that crush me in the piano-dropped sun. The accents of the aides changing daily. Gravity holding us all in our places like a tragedy play. How I sat through ten years of therapy to prepare me for this, and can remember absolutely none of the skills I learned. How faithfully I wrote them down. How nothing can ever prepare me for this.

Pre-pare—To anticipate the slice. The cutting away, the excising of her breath from my own. These internal landscapes. The touch of her softness. The dimming colors of already-fading memory like a sunset. To wake crying at dawn. To sob before rising, to move toward this day of freshened hell, to feel this lost and sorry for myself at the tenderness of my own heart. How the sound of my crying is just like hers’ to my ears. Gotta hold on, but I wish someone would hold me. The slow dissolve, the good wood supporting me, freefall off french provincial cliffs still holding her gold and diamonded hand. Soft as this landing cannot be. Soft as a field looks before poking through. Soft as a rainbow draped over a granite mountain. Hold me like that for just once more.

Their sleep-curved forms in the ghost light. Their breath turns, twining these walls, remembering better days. Still, they are happy, often. They are in love in a simpled-down peace. They are pared back, they are paired up, and I, the singularity watching them sleep, feeling a little jealous. I always have. This kind of love, some childhood belovedness that’s haunted my dreams blooms here, in this warm soft bedroom that's not mine, where I can glide in, lie down next to her soft curved form and cry.

Pushing a wheelchair over the golf course, the sand traps are the worst. It's 100 degrees and a million percent humidity at midday. Borrowed the wheelchair from the clubhouse to take her to the neurologist, where she is furious with me because the doctor only talks to me, only listens to me, and she is deaf and it sucks. I push the wheelchair, wanting to meet her suffering half-way, take it on, dilute it with my own.

But it gets way worse when I bring her back home and try to take him to the bank. Same borrowed wheelchair. He needs to sign a form so I can withdraw their funds. She flips out. Culled from the herd, left behind, counting for less than nothing—“I'd just like to be asked to manage my affairs!”

Fine, Ma. Do it. You're out of insurance, Iveny costs $11,000 a month, here are the car keys—go to the bank with Shelley and fix it!

“You don't know what it's like” she says, “wait till you're 140 years old and nobody wants your opinion and nobody talks to you.”

Together we hold on and cry.

Mama just cannot fall asleep. She wanders through the house, hallucinating. I too am awake all night, worrying and herding her back to bed. Last night I had to lie to her about a valium.

“It's a B12”, I said, and then I shoved it into her mouth. She spit it back at me. After a few more moments of near-wrestling matches with her, Ivenny steps from the shadowed doorway, pulls me out of the room. “If you keep being with her, like this, you will get sick.” Is this a warning or a Haitian voodoo curse?

When I shoved the valium into her mouth last night, she was so surprised. I was too. We struggled awhile , and then she sat up and opened her mouth to show me it was gone. She had palmed it. I took it out of her hand and stuck it into her mouth again. The second time I shoved that valium into her mouth last night, she swallowed it. Shaking her head, furious. Still she never slept, shaky as hell but up all night. I gave up at 3am, put in earplugs, swallowed a Xanax and smoked pot till I passed out. This morning, Ivenny says I was the only one who slept last night, and suddenly I appreciate the fucking hell out of Ivenny.

Time for me to leave, alone for the airport. She's been asleep now for 2 days. I cuddle next to her—(is this another last?) I can't stop crying. This softly dim place is the magnet to my heart, my one true north, the best place because She is here, but I’ve got to get back to my job. Follow the trail of this one tear, across the bridge of my nose, spilling down my tilted face. Follow the drama-filled narrative of Daddy’s sleep talk— “Mumble mumble seven minutes! Mumble mumble, bullets!”

I’ve been home on my mountain for four days now. Thoughts of Mama do not stop. She's hallucinating her ass off. I'm struggling not to call, because I can’t hear her and she can’t understand what a phone is for. Ah, Mama. Tangled veins and shared blood and holy patterns all flaunt my escape intents. My unconscious commitments chase me in circles as I deny them, all day long. None of these nursing homes I’ve spoken with on the phone want to take Mama because she’s on so many heavy-duty psych meds. This makes her a flight risk.

“She’s not!” I argue. “She weighs 91 pounds and can’t move her own wheelchair. She’s totally docile; she’ll be good.” She just has to—you HAVE to, Mama! Again, I am fiercely committed to something impossible for me to control.

Time to tour the actual nursing homes with my pal, Jan. We walk, side by side, and she holds my hand, passing through long corridors of other people's destinies. The smells there. The ubiquitous, caged birds in each nursing home lobby. Who's idea of comfort are the tiny, bright and beautiful caged birds? Who's idea of a good ending to a long life is this inevitable shit at the end; so many of these people trying to die and not being allowed? Life. It's like this awesome gift we receive that turns ugly and terrifying over time in our wrinkled, spotted hands. It's like the smell of pee overwhelms the smell of springtime. I think sixty-six, this is my perfect exit age. I think, take me before it gets so lonely, so broken, so desperate, scary and stubborn—hanging onto a cage that shrinks while you’re at the mercy of aches and unending anxiety. The tiny birds flit and crash softly into the glass.

Death waits for his assistant, old age, who’s coming. At every party, all my aging friends seem to speak of is diagnoses, medication, surgery, complications, dying parents. On the classic rock station, all the commercials are for vaginal rejuvenation, viagra and botox. Oh, I am preparing to be done with preparing to be done. I don’t want a plan to meet old age. I want a better plan. I take myself by the hand, slightly spotted, but still pretty, and turn from that moving walkway. I will be in charge of it, by my own peaceful hand. 66 years is so much! My life’s been so long, so full of adventure and transformation compared to my Mama’s 94 years. And when I die, bury me naked, standing up, with a banyon tree planted on my head. And set all the caged birds free.

When I get back home there’s a phone message from her aide agency.

“We had to take your Mom to the hospital.”

The world teeters. The stranger’s voice says something about dehydration. i know that’s the least of it, but still, I feel like at least she is safe.

Mama's in the hospital, and when I finally get through after 12 minutes of listening to the ubiquitous recorded message about how much they care and how great the quality of their care is for my loved ones, I reach her, and she’s utterly freaked out—

“Where are you? Where's Daddy? Where am I? Who's phone is this?!”

I just spoke to Daddy, alone in the house. He says “Soon as Mom's out of the hospital, we're coming to Colorado.”

Bless him. He remembers. At home, I try to stay busy, to stay helpful. I call the airline while she is tied to the bed, tearing through another unmapped and unmappable day. I am so full, I cannot move fast for the sloshing. So, carry water. Pour water. Moon baying full at the window, clouds pass over her face to remind me of change-making, all things freshened continually promises the river. Tomorrow I go to Florida at midnight.

She sits in a wheelchair looking like she's had a stroke, all droopy shoulders, mouth and eyes. She's talking to her therapist when I burst through her door.

I hear her say, “I'm a strong individual. I just keep telling myself that.”

That’s a more coherent sentence than I’ve heard from her in awhile. Maybe it’s going to be ok. The rabbi from hospice comes and tells me in the hallway, that she’s dying. The hospital diagnosis is Terminal Alzheimers. I can get her on hospice at last with this diagnosis. I get her discharged to my care.

She comes home in an ambulance.

When we are all together again, she says to us, “Oh honey, you missed it! I was in a parade! Everybody was watching and cheering from their balconies as i passed by, and I was spinning around inside the red flashing lights!”

And then the illumination in her eyes dies, and that’s the last thing she is able to say for a long time.

Watching Daddy deal with her not putting him in the center is something. Welcome, Copernicus. And I too, so used to her attention, feel so scared when she gazes, slit eyed, past me.

Shelley greets her at the door: “Hi, Lil! Hi Sweetheart! How are you feeling?”

She won't look at him. I roll her out to the hot porch to do what she loves so much— watch the storm coming in warm and soft and wild. She wants out of the draft. Pulling at tissues and the neckline of her housecoat has become way more interesting to her than focusing on us. She is retreating to what’s inside. Way more interesting than us.

She finally looks up and says, “Do you ever get the feeling that everyone is looking at you?”

She's still funny. She shakes my hand and says “Sholom Aleichem.”

I go to unpack my suitcase. Again.

Maybe all her relentless plucking is her unconscious way of removing a lifetime here, physically tugging it off her body, and pre-paring. I sit in the storm on the catwalk, smoking and watching Ivenny cook in the kitchen. Watching Mama in front of the mirror. The wheelchair has become a part of her profile now.

Love: we claim each other. We are here for each other. We belong to each other. That's the deal, I tell them both. I remember love. It’s in my body now, memorized forever.

Love is my mama's softness, and me growing patient enough to tolerate her putting on 4 pairs of panties, hallucinating for 3 nights in a row.

Love is my Dad and I talking, and him showing up so beautifully, asking out of the dementeted blue: "When are we going to Colorado? I can't wait!"

Love is remembering what a great pal he was to me, how sweet our connection was when we were best pals, when i was a tomboy and he was an athlete and we loved each other simply.

Love is the beach on a sunday, when I finally get away to stand, hip to shoulder with a crowd of strangers in water up to our ears and be bounced as a crowd, as one, by the tide. Love is banyon trees and ficus trees and grapefruit trees in a crazy feral golf course, netted with jeweled dragonflies.

Daddy’s’s in his tv chair when I wheel her into the den. After trying and failing to get her to smile, or to look at him, he whispers to me, “Do you think she even knows who we are?”

He thanks me profusely each time he sees me, and this morning as I climb into bed with them he whispers, his voice bottled in a strange anxiety “Not today, right?”

I don't know what he's asking. If she's going to die? If we're going to move to Colorado, but I just say, “No Papi. Not today.”

“Thank you, honey. It's been a wonderful visit.”

“I just got here, Daddy.”

On the other side of this bed, she trembles mightily for a moment. Papi has started pooping his pants and the bed. Mama turns over for another flake, another slice of sleep. This morning, the hospice chaplain called, the social worker too. They delivered diapers, and Sandi reserved a car. She comes in late tonight to support me. Here comes the wheelchair and hospital bed.

Ivenny just quit. Holy shit. It's 5 pm and Friday. What will the agency do to fill her place? They say they don't know. Why? She won’t say. Just that she’s done. I’m eating Ivenny's Haitian cumin salmon. I sit alone. Daddy doesn't want food and went to bed. I’ve never seen this before in my lifetime—the man is an eating machine! Ivenny won't sit in the kitchen with me and won't let me sit in the dining room with her. It's very lonely in the Land of the lost Chezars. I cry with my back to her, eating the good salmon.

Mama is currently auditioning for a lead role in Awakenings. Yesterday brought a new aide, Mary Beth, and that magically changed everything. Mama walked into the kitchen with her walker after ten days in the wheelchair. She sat in her chair and after eating three tablespoons of boost yesterday, she ate a bagel and cheese and three cups of juice, tea, and then asked for peanut butter. She walked back to her room and then did it again for dinner.

“Wow—great job, sweet darling! How do you feel? Tell me something, Mama.”

She says, slowly, carefully, “It's a wonderful thing to open your eyes.”

She stares at MaryBeth, “They had me locked in the coffin, but...how did YOU get in here with me?”

I am trying to just give love. Learning to relax in the dragon's mouth. Find peace inside the haunting bright blue flame of the dragon's lips, curl up to sleep tucked into the wicked jab of the dragon's teeth. Cos this is life on life's terms. Black and blue iv scars, shit-stinking carpet, Ivenny leaving us, all of it.

Been here one week now. I wake, heart pounding this morning to a doubt that Grand Canyons my soul. She's not going to make it. She's on one of those manic downward tears. She's not slept in three days and now she will sink down and sleep for two or three in a row. How can I leave now? How scared is Daddy, and what to do with him?

My cousin tells me, “Listen, don't let her die next to him.”

And I think but they’ve both been dying next to each other for 25 years. But I need to talk to him. I need to help him through, if I can. I’ve swallowed an Ativan already by 7:30 am.

End stage dementia means I can hold your soft grey head against my face and you don't know I'm here. Means you tug and pluck incessant and slit eyed at fluffy nothings and meaning recedes with speaking and orientation and walking till there are just these small motions signifying everything that was ever you. The moans, the rocking, the brave struggles to rise.

Norma says on the phone: “She's traveling across the veils and that's her journey. It's not your journey. And we get crazy when we can't tell the difference. She's doing exactly what she needs to do. Go home.”

Go home.

This is my last night here. I go sit with Mama, who is slack-eyed and vacant. Daddy, as always, sleeps softly. I tell her I love her. I cry, quietly. I go off. Come back in a few minutes to stand in the dim doorway and wave to him across the darkened room—tentative—not sure if he’s up or will see me. But he waves back. I go over to him.

“How you doing, Daddy?”

“I'm alright.”

“We're all going to go to Colorado soon.”

He smiles a little. “I love you, sweetheart. God bless you.”

“I love you too, Daddy.” So hard.

“Not without pain” says Sandi when i collapse next to her in the other bedroom to weep.

Grief is private property. It's a gated community. This grief is particular to me alone. No one asks or wants to know, really. I see it in my friends' eyes. I am trying to de-construct my reactive brain. Feeling the tiny silver fuses popping in my throat and chest, the rev of fear in my belly; I’m slowing down, breath first, to keep from leaping into reaction. Facing the uncontainability of the unknowable. Facing the tsunami of that and living to describe it only to the page, and so, to myself.

I do this one easy thing once home. I water the plants. I do the next. Fill the jugs from the big purple barrel as clouds mass in the sky. Carry water into the house. Thunder coming now. Rain will fill the barrels and the cycle of life without plumbing will be restored. Weather revives us, like the moon. Restoration—what is left? I am so full of all our lives, I cannot move fast for the sloshing. So, carry water.

Exit, Stage Left

Went to 2 support groups today in Boulder—for Alzheimers' ,and for Caregivers. By the time this is over, I will have both their social security numbers memorized, as well as phone numbers of doctors, neighbors, insurance agencies, lawyers, & elder care agencies. Also, all the data of their mortgage, Medicaid, insurance policies (Medicare, Part B Part D), their banking practices, his retirement pension, their medicine dosages, their vital signs and my own blood pressure, as well as relevant instructions for faxing, scanning, and documenting every piece of perilous paper ever signed with the name, Chezar.

Here is life, levitating between a rock and a hard place. Here am I, head down to the winds, feet pointing steadily downstream. “Please”, I beg Manor Care, “just Take Them!”

And at last they say yes, they say Come. I leave day after tomorrow on the red eye bound for Florida for the last time. The crank begins to turn for real on the impossible-seeming plan, to stay four days, and bring them back with me on Friday. The Great Chezar Westward Migration begins now. The lists, the organizing, the outrageously tough work of the past year and a half paying off. This the cherry on top of my hip replacement and the flood.

Florida

Here we are. Mama and I are lying in bed, snuggling, and I tell her that my cousin and her husband are coming tomorrow. I don’t say that they’re coming to distract Mama and Daddy so I can empty out their drawers, their closets, and somehow pack stuff up. This is a big secret plot, like the asteroid, but more grounded. She’s so excited to have company, says we can bring food in.

I tell her I’ll go get Entenmanns.

Her eyes flash open "There's still Entenmanns?!"

I have to get up and write this down.

There’s so much stuff! I’m running all evening to cram the contents of closets, drawers and bedrooms into the tiny incinerator, into the darkness i race back and forth as fast as I can. Being stealthy, in the deeps of night while they sleep. Trucks-full of their lives—shoved in there, ruthlessly tossed to be burnt up garbage. Overwhelmed, imagining all the energy, the money and desire that they’ve spent collecting an identity, making life beautiful, only to have it all culminate in some overwhelmed only child burning it all down. Gotta fight off another panic attack.

Tonight, Hilda down the catwalk, with her walker and colostomy bag says to me “Your dad musta been a real player.” In her heavy Brooklyn accent. And I think oh yeah, at 92 years of age, he’s still hitting on women. The cross my mama has borne which made her so crazy, over something so elemental that is Shelly. Instead of making peace with it, or leaving him, she took a big hammer to the circuit board of her fine mind and smashed and fused and sparked the circuits towards this one response— jealousy. Fear. The reactive brain. Control. Suffering. Oh, teach me these lessons, the wanting to suffer, the stress and the worry as evidence, as a a cryptic imitative form of Great Love, when truly, suffering is optional. And here is one more great message of This Time.

One last really long fucking day of packing and getting and bringing and dumping and dealing and driving. Then more wild dumping extravaganzas—between diamonds and gold and garbage and raging, and looking for all the cash she has lost in this place over the years. The aides have reported over and over that she goes to the bank with them, withdraws a bunch of cash, and then the next day, it’s gone. But i never find any of it. Bet she flushed it.

I will be haunted for years by the tons of material world objects, taken by gravity’s shoot and loudly crashing down the steep sides of a dirty incinerator to be gone. Somewhere. I’m hypnotized by my tasks, in a trance, then shaken to a halt by photos—all familiar as stories that I swallowed, as pills that I swallowed, and who are all these sepia faces? Russian Jews, dead strangers, ancestors who’s names i don’t know. And exotic trips taken, and my more—my face in so many iterations, familiar cousins, and so many dogs—I throw them all into suitcase, take every single one, and albums of cards and love letters. I throw away so much, but not these.

Mama lying there, fuming “What are you planning to do with us?” Daddy, yesterday inviting the cousins to come to Colorado to visit, still the big-shot, bless him, saying he had a furnished room for them. I imagine Manor Care, imagine what it will be like to have them inhabit that particular tiny cage. I think that it's up to Daddy. Mama will place herself as she does, totally at the mercy of his actions. Oh sunset sky, fill me with love and flow, ease to fade, one cloud at a time. We're almost there.

In the Sky

Here we are. Holding onto a tired twined rope, hanks fraying as we go, winged before death, holding our breath. Holding hands and hankies. Chugging through varied, random schlepping, a crazy rush-job as we say in my tribe. Tribe of three. Ativan all around. I have Haldol too, and doctors’ instructions from three doctors, for her psych meds.

We checked in under a spell of so much grace from every person we had to come into contact with. I have a card that reads— The person I’m traveling with has Alzheimers. Please be kind. They were all lovely, all these strangers. Everyone’s got a demented beloved it seems. My head a buzz of last nights’ sleeping pills, Ativan, gin, and Ativan. Atta-girl! Falling through and rising on tiers of blue. We’re on an airplane! This is truly fucking happening!

Me in the middle seat, Mama at my right hand in a babushka, and both of them in their softest blankies. Bald and deaf and age-spotted, in diapers and wheelchair-bound, Colorado-bound—The Dream. And Sabrina on the other end, circling Arrivals in her car with water, Gatorade, fresh love. Paul’s in his car too, waiting to grab luggage—there is so much fucking luggage! Paul will take Papi to the toilet and be the cabana boy. I feel lighter than I have for months, but I know in a segmented somewhere how hard this next piece will be. Piece and then piece and then peace, a quilt of next nows building.

I tell each other them, separately, that we’re doing this for the other one.

Telling Papi, “Sure— we’re going to my house. You can stay as long as you want. We need to get rehab for Mama”.

To my mother I say, “Daddy’s P.T. sent us here so he can get stronger and get back on his feet.”

Oh god, I wish these lies were true.

After sleeping through much of our morning trip to Ft. Lauderdale, all of TSA and boarding processes— now, as the four hour trip begins, and after a dropper of Haldol each, they’re wide awake. He reads a magazine and she runs her fingers over the soft blankie on her lap. Suddenly, she has to go to the bathroom. She’s wearing 2 diapers, but she insists, loudly. I somehow get her down the rows—practically carrying her—and we can’t close the door because she won’t sit down on the seat, and I have to hold her around the waiste as she hovers over it, and she can’t pee. I pull up the diapers. We trudge back. She’s curious, alert. We have two hours left.

The next piece is coming—getting them to Manor Care and then leaving them. How will I ever just leave them there? And it’s all happening, but too fast. Rescue Remedy, heavy thrum, motion mattering more than anything has mattered as we zoom west into the next now. I am recalling heavy stones, placed by backhoes, one at a time to hold up the ruined roadbed through my destroyed canyon after the flood. Stone by heavy stone, the ease and flow of the river below. One step at a time. I am becoming a solid wall of stones. I splash as river, easily meadering below, free at last on a fucking airplane. For now.

My nervous system is carbonated. My nerves clicking husks vibrating like cicadas. My belly lurches all day in tune with tasks and ringing phones. They said it would be hard. By now I’ve left the tip of the iceberg and am heading into for-real iceberg territory. I’m surfing the cold density of iceberg, I climb down the sides of the iceberg, hand over hand under heavy dark waters, kicking for some sunny shore, weights tied round my feet. My heart.

Arriving

Boulder Nursing Home

9/20/14

Well, here we are, the three of us together, finally. Unpacked, upended, rear-ended, sacked out, acting out, outrageously confused, fused to loving me, gravity-defying final act of the Land of the Lost Chezars, Boulder Edition.

Nursing homes. Sad places, surprise studded, freedom denying, death defying, impossible dreams and where they come to lie down on the seeded cage floor of gorgeous & exotic tiny birds who symbolize nothing better than wired marvels but soothe nevertheless. My father, open mouthed before them. My father, who at 8 pm demanded the car keys, cash and to go gamble. My father, the least of my worries, insisting he has a car and a game set up, the fellas are waiting for him.

"Whaddaya talking about? Of course i have a car!"

Supper freaked him out, surrounded by old people in wheelchairs, just like him, he hated it. He's never been good with sick or suffering ones, and he started in on my mama, "Come on, Lil, let's go." She was lying down, exhausted after the plane ride that i don't even remember, the details mushed with the packing and the cleaning and the immensity of the act of moving them.Me on Ativan. Attagirl! Get through. Only this.

"Come on, Lil!"

"Daddy, where are you going?"

"We're going home. Come on, Lil!"

The aid is trying to distract my dad, to calm him down and to protect her.

But, by now she is struggling into her shoes, struggling to focus her eyes.

"No dad, home is 2,000 miles away. We flew here on an airplane for 4 hours. Remember?"

"Whaddaya talkin' about? Where's my car?"

"You don't have a car anymore, Daddy."

"Whaddaya talkin' about?!"

And on it went on and on, Mama sitting up, lying down, till the nurses separated them. Took him to another room and parked him there.

“Lie down with me, Baby. Let’s cuddle.” Says Mama.

She went right to sleep. I held her. Hours passed. I wandered outside, smoked a bowl while she slept the long trip off.

Manor Care is a big circle, lots of open doors to rooms like hospital rooms, the iv's, gloves and masks, the machines beeping. Nurses and aides. Folks sleep in hallways in their wheelchairs. Herds of dozing oxygen tanks. I was looking for my father, spying round corners, not wanting him to see me.

He was a hard-core wild man. I figured if he grabbed a wheelchair, he could run with it. When i finally found him, he was watching a black and white Jerry Lewis movie on a big screen all alone in a big darkened room. I went to him.

"Daddy..."

"Where's your mother?"

"She's resting daddy"

"Did she go home?"

"No, she's down that hall." i pointed.

"Oh...I thought she went home.” Dreamily, he says, “I thought I would go to New York to look for her. Go to the places where we used to hang out."

"Daddy, that was 50 years ago!"

"Yeah, it wouldda taken some time, but I'd have found her."

“You love her so much.”

“I sure do!”

"This is a pretty nice place, Daddy"

"Yeah it is." He looked around.

"We’re finally in Colorado, Daddy. I live right across that street and up the hill", pointing vaguely again, lying a little about the distances.

"You do?"

"Yeah, and I'll come see you every day, Daddy. I want you to be close to me. I love you. Do you think you could stay here with mama and me?"

"Well. I think I can try. I'll try."

"O.K. Come on; let’s go see Ma."

I told him she was sleeping and he needed to let her sleep. I wheeled him into her room. Her bed was lowered as close to the floor as possible, and there was a mat next it for if she rolled off, cos nursing homes consider bedrails "restraints", and won’t use them. They had had bed-rails for many years in their home, and this refusal would turn out to be a big problem.

He leaned over and looked at her dead asleep and said,"She’s not sleeping"

"Daddy, she's sleeping."

"That’s not sleeping. Hey, Lil!"

He lunged towards the bed, tripped on the mat and fell right on top of her.

"Oh sweetheart! Oh, Baby! I missed you so much!"

She's pinned under him and squirming.

"I really missed you! Did you miss me?"

"Not really."

He lies down next to her clutching her, grabby and graceless, and she shrugs and lets him. The young aides fill the room, swooning at this dramatic display of love, as he kisses her fingers and tells her how beautiful she is. How he loves her and he missed her. They sigh and hold each other. The aides think this is so Romantic!

"How long were we apart for, Lil? It felt like weeks. Has it been weeks? LIL?"

And she pulls herself slowly back to consciousness, tells him groggily that she was going to find the phone numbers of the wives of the guys he plays cards with and track him down like that.

"So.... didja win some money?"

Omigod she thinks he was playing cards!

Next day, both of them were confused and grumpy. When i left i asked her if i could bring her anything when i come back tomorrow.

"But you won't." she said.

"Sure i will, Mama, what do you want?"

Her eyes sunk into mine,

"A little poison."

Scorpio Full Moon

Chevra Kadisha is a beautiful Hebrew word. In English, it’s The Holy Jewish Burial Society. The volunteers who perform the final rites for a religious Jew— the ritual washing and dressing of their body while reciting the ancient prayers and verses from the Song of Songs. These strangers come, and they sit with the dead, with The Body. They’ll sit with you, Lil, from the time of your death till the time of your burial in the earth. Your casket won’t have any nails, they tell me, because metal is a weapon of war and war has no place here.

Full moon in Scorpio. Yesterday, Reb Patrice, a lovely rabbi-stranger stood over Lil and I held her hand and Shelly lay there, willing himself to sleep, and she said the prayers for the dying, Jewish last rites, and I’m becoming Jewish at last in this, and Lil stirred a bit from her struggles between the gateway before her, and whatever is keeping her here—gravity, entropy, fate— clenching and mumbling and wringing her hands.

I found out 2 days ago that I can bury a body on my land, if I have more than 2 acres in Boulder County. I wouldn’t have to lose her forever to be planted next to her father-monster in that terrible giant industrial cemetery in Queens where 5 million Jews are buried in less than 10 acres. Unimaginable.

I went to the mortuary, where a sweet man in a suit filled me in on the many details of the process of burial. What the hell do I know about burying a coffin in the earth? He had heard that it was possible for a body to be buried on private land—it has to be more than 2 acres—but he’d never participated in such an act.

" So, um, how do you plan on lowering the casket?" he began.

“Uuh, I dunno..”

“Yeah…O.K., Well, how you going to fill in the hole?”

“Uuh, not sure…”

“Do you want a concrete cap or were you just planning to mound it?”

I had not considered any of these details.

Mike is a patient man, and kind. Turns out 6 strong folks with heavy-duty ropes, 3 on either side is traditional, but you’ve got to be careful to lower the ropes together so the coffin doesn’t tip, or we can have a lowering device.

Turns out you can cap the top of the mounded grave off with concrete to prevent it from sinking, or you can just mound it in earth and just see what happens. I like that idea—a mound—ancient, humble, submitting to Nature’s ways. Burying concrete in the ground is an awful thing. Bad enough to sink my Mama into the cold winter earth, alone.

He told me more about the Chevra Kadisha, mostly how they rip out the insides of his beautiful and expensive satin-lined coffins.

Then back to the home and a visit from Sandi, and Lydia—the-golden-doodle who lay with Shelly in bed, his hand on her paw and her head on his hand, both of them conked out like little kids at a party, too full of sweetness to face the finality of it All. Mama slept, restlessly next to him. When i was alone again with them, I had just enough time to catch the hospice's magically-timed training about Jewish burials—and I learned a lot more about the mourner's path. It was all volunteers and social workers and me.

Dying is the background noise. I stand in the silence of it. I can barely handle being away from her now, it’s like a pressure pinching on me. I couldn’t sit there for long, apart from her still-living body, listening to a lecture about her dead-future-body, and I left from the front row in the middle of everything, mumbling an excuse, headed for the nursing home, but then it was just too hard to stay in their tiny room, ‘cos she was so restless, and so tormented, clutching her nightgown to her breasts and mumbling, 'Papa! No'.

Her father had incested us both. She’d forgotten, even after I told her at 6 about my own abuse. She remembered hers’ at 76, deep in therapy.

“Papa, no!”

Later, their deaths would hit me in waves. Not a flood, but water lapping steadily round my ankles. Mama, so frightened of swimming told me my whole childhood—“You can drown in a thimble-full of water.” Maybe grief was like that.

I had to leave when they started to turn her and prop her — it felt so disrespectful, like they are trying to comfort the family by keeping her skin from breaking down—for me, for themselves, and not for her who just wants to lie on her back in deathless torment, just waiting for it to come and save what’s left of her mind. They put her in hot plastic booties to protect her heels, and I took them off and then i split.

I left and came home under the Scorpio full moon, sobbing, wailing, the road a blur, my very spirit feeling stomped, burnt, all rumpled and torn. Screaming out exhale after exhale as loud as I could helped clear my head of the images, and the car rocketed through the darkness, tragedy reflected in the ruined canyon, stones vibrating to my voice, engine shuddering with my heart, an arrow, lost and shuttling through the cold, lonely night.

You're supposed to close the eyes and cover the faces of the dead because it's disrespectful to look at someone who can't look back at you. Mama can't look back at me now. People say she can hear me, but, I'm not sure about that. She is so lost in her final big bummer, she is so consumed, as she always has been, with her own suffering.

It’s a cliché that I’ll miss her, I’ve lost so much of her already, yet it’s true. I’ve lost the shining best of her—her sense of humor, her ability to chat daily on the phone—her capacity to talk to me at all—to recognize me, to love me, to hold me, to want my body pressed against hers'—our so-similar bodies, the shape of our skulls, the roof of our mouths....The last words she said to me as I tried to lay with her on the narrow bed in the nursing home: "Get out of my kitchen!"

She’s so gone from me now, my heart stretched and broken with the distance as I try to release her and hold her at the same time. The greatest respite I have now is knowing that she’ll be buried, snug and safe in the dark earth of Laughing Bird, right up the mountain from my front door, overseeing all this beauty, witnessing me everyday, in all weather, living my life here.

At the Chevra Kadisha presentation they said that sitting shiva is all about structuring time, which is so unstructured in the experience of The Great Grief.

I had a backhoe dig my Mama's grave this morning. Now I’m here where she lays dying. Papi, less than 2 feet away, wrapped in his own silence, in memories, dreams, whatever holds him now, all the curiosity focused in the many framed photos of us there on walls, leaning in to see. This too-small room is The Land of the Lost Chezars’ history museum.

I return, in breathless despair, to my most recent memories of her, which are the most terrible ones of our shared lives. I’ve found a woman who will perform a ritual a release for her, Sandy—a healer who’s a shamanic Jew. Mama moaned and roiled and thrashed gently, like water in a tank—

"Papa. Papa!"

Sometimes she screamed, and her voice was becoming so ragged, so exhausted yet insistent, as she couldn’t be in life. Her anguish splashing all over me, wetting my cold feet. And I’m so triggered—this is so hard!

We prayed together, holding hands, Sandy and I, for a letting go of this suffering, for a disconnection from him forever, for a resolution that was good. I prayed to be a strong, giant wind that would blow his soul into outer space. I prayed that he be totally gone from our black and blue bruised memories forever so we could both have peace.

When i can feel this, it will be fucking outrageous.

Now i am back here, sitting on the floor, spinning inside her suffering arena. Papi lies sleeping or pretending to right next to us. Still she is internally thrashing, moaning "Papa, no! Papa, no!" I’m huddled close to her, saying loud in her good ear, pressing on her attention, desperate to redirect, to save her again, at last—

"Just walk away from him Mama. You don't have to stay. He’s gone; he’s gone. I'm right behind you, let’s leave this room, forever."

I say, "You don’t have to suffer like this. Let’s just walk away.”

She starts to quiet. Just a low moaning.

"I’ll be with you. I’m going to take you home with me. You don't have to do anything. Just let go. Let it go".

She resumes moaning and thrashing.

It feels wrong to interrupt her process—maybe she needs to have this experience. Though why, I can’t imagine. Some mystical re-knitting; some warped version of release. Maybe she isn't suffering, maybe that's a story. Maybe this isn't hard for her, maybe it just appears that way to me, through my filters of this event, this living that I’m sharing with her in the moments of her dying.

I remember the 12th benediction of the Amidah, the central prayer of my childhood temple worship services—“May all evil be destroyed in an instant.”

Walk with me Mama, please, hand in hand through this nightmare, like leaving a burning building from the top-most floor as fire consumes the walls. Plank after plank across the green room towards the closening stage door, the deep consciousness of winter taking us piece by piece.

I turn to Daddy. “How you doin’, Daddy?”

He always says he’s fine, but tonight he says he is not o.k. But he won't say more.

"Daddy”, I tell him, “ Mama's really having bad dreams, about her father".

He closes his eyes.

Says "Go to sleep, sweetheart." Says,"God bless you. "

Once home, I realized that i have this story that if she is not at peace when she dies, her spirit will haunt me and everything in my life will be in danger of being slimed with the dark and dangerous vibes of my childhood..I’ve worked so hard to clear the toic memories, but Mama’s dragging the loaded sack of my grandfather's evil energy with her like a comet tail. Maybe when i bring her here, maybe he’ll follow right behind us and the two of them will continue this cosmic struggle right up the hill from me, forever. the thought sets off a fresh panic attack.

I sing a chant, over and over again, and I pray it like incense over her body—May all evil be destroyed in an instant.

There, up there in the freezing rain of November, is her grave. Empty. Waiting. A big storm is coming tomorrow. Is this crazy? It’s going to snow all fucking week. And we need to bury her with shovels. Where will all these people and these shovels come from? I haven’t put out the call yet to my friends. Four feet by eight feet by six feet deep is a lot of dirt, but the backhoe dug out even more.

The petrifying story along with the enormity of what i’m about to do chase each other round and round inside me. He’s here, he’coming....he’s coming up.What the fuck am I doing? Nobody in my family’s ever done anything like this. I’ve never heard of anyone burying a body on their land. It's a dark,moonlessnight and very late and I'm so fried in my physical and my emotional body—I’ve just got to get home and rest. So torn between wanting to stay with her and getting the rest I’ll need for this next laborious doing.

Sunday the 10th of November

Well, she almost made it through the weekend. But, at last I know she would never haunt me, never bring him here to hurt me. I am her very favorite human and she will be delighted to be close to me. And maybe she fought him off so hard to shove him out of both our lives, forever. This was an epic battle. Oh, Mama! She is peaceful at last.

Sandy did two sessions to release her, sent me out of the room yesterday, and when I returned, my belly twisted into knots of the final rope, the spell had worked! She lay there, stilled, so relaxed and peaceful. Her fists unclenched, her lips closed over the terrible sight of her bared teeth. Her brow smooth, her heart calm as last. Comfort floods me in the face of the holy finality.

Papi

The day that she died, I told him three times that she was dead. Each time I sobbed, even as I tried to hold it all back. Each time, he was utterly shocked and so terribly sad. It took a long time, but finally it all just went away. Dissolved into something like a softening demented acceptance.

Mama died at 7 am. The phone rang from Hospice. Joy drove and we rushed down the canyon through the thickening storm to the nursing home. I knew of course that she was going to die; I wasn't rushing for her—I was rushing to get to him.

We got there, and as we hurried towards their room, I passed the dining room, glanced in, and there was Shelly. I went in and knelt on the carpet beside him.

"Hi Sweetheart!"

“Hey Daddy, how are you?”

“I’m great, darling. Sit down, wanna eat?”

“Uhhhhh.........I'm just gonna go see Mama. I'll be right back.”

I raced down the hall to their room. There she was in her narrow bed, dead. Holding the flower, the final hospice gesture, clasped in her thin, still hands. Her face is smooth, the hair brushed back.I sit with her awhile then go get Daddy.

“I need to talk to you.”

I wheeled him to her bedside. He didn’t look down, looked instead to me.

“What is it, Sweetheart?”

“Mama's died.”

“What?! She died??” His face contorted with the shock of it all. She, who'd been dying next to him for more than a year now.

“Oh, my god! How terrible! Oh my God—I didn't know she was sick!”

Then he was wiped out and had to lie down. I helped him, both of us weeping, from the chair to the bed, and went to kneel by her side. There's this me-sized gap between their beds, where the home had forced them apart, over my still-live-but-in-full-protest body to separate them, and I was down there apologizing to Mama, and forgiving her—it's a Jewish thing, I read about it— and he woke up.

“What are you doing?”

“I'm asking Mama for forgiveness.”

“Why?”

“Because she died. It’s a Jewish thing.”

“She DIED???? Oh my God, she DIED? How? What? What did she die of?” He cries hard, he shakes and roars like a sea lion, and then he whispers in a frail voice, “I just gotta lay down. Oh, oh I'm so tired.”

Then the guy from the mortuary, who would lose her body soon for an hour or so, shows up to take her. And I wake him again, braced for it this time.'

“Daddy, do you wanna say goodbye to Ma?”

“Why, where's she going? Wait, I'll go too.” He starts to move towards the edge of the bed, bends for his shoe.

“She's going to the mortuary.”

“What?! Why? Who died?”

And so, I said I will never fucking do this again, hurt this sweet man and make him cry, for nothing. What is even real? If i tell him and he forgets, does he KNOW? If he loves her and she loves him and they lose each other through some white lie in the end, are they ever reunited? How is it that this shit works? If they lose each other having forgotten each other, is that the last goodbye?

And, does any of this even matter? To be alone, in the end—I have felt so alone in this life. And now, I have nothing but space. I am nothing but space. What I want is to tell him, to have company in this loss of our shared great beloved. But he never asked again. They moved him into her bed and moved a stranger into his bed, and still nothing. The photos of the three of us on the wall beyond the foot of his bed confront him all day and night long. Nothing.

A month goes by, where I see him everyday. Loads of time spent together. Nothing.

And then the other day, a terrible day I'd spent crying to strangers far away on the phone—repeating over and over again, “My mother died. My mother died”

To her creditors, the collection agencies, to the bank and doctors’ offices and hospitals, and then photocopying and faxing and mailing her death certificate, over and over again, each motion wearing me thinner. That day I woke him up, I always have to wake him now, he sleeps constantly, and he said, “Where's Mom?”

“She's not here, Daddy. Do you want to put your shoes on or do you want me to put them on for you?”

And that was that.

For now.

If he knew, maybe it would be ok for him to die. If he knew, he would be grieving along with me. If he knew, I would feel less crazy and alone. If I tell him, it would be a very selfish thing to do.

One morning, I took him out in his wheelchair to a pretty spot overlooking the Flat Irons, and I tried to have The Talk.

“Daddy, what do you think about Mama?”

“Oh, she's so tired. She just needs to rest. But honey, she's getting better.”

I've told this story so much, and the other, earlier one, about how he was when they were separated that first night at the nursing home. In the repetition of these memories, in turning them into performance pieces I feel safely distanced from the terrible narrative playing on a loop in my actual heart.

It is all in the air. All in the air. My heart summersaulting, then crashing like a kite in the air.

Yesterday i woke him up, and he smiled

“Hi Sweetheart!. Oh, boy, I have such a story to tell you. It's a really big story! You're gonna love it!”

“Tell me now, Daddy.”

“Nope, i can't tell you yet cos its not finished yet. But i will tell you. And you'll love it!” He was so excited.

“Oh daddy, tell me, i can't wait. Does it have a happy ending?”

“Oh, yes, very happy darling. I'll tell you tomorrow.”

Later that day i asked him to tell me the story.

“What story?”

Of course he didn't remember. I wanted to squeeze him when he first told me, like a tube of toothpaste, and see what's in there. What is in there?

5 weeks later —

I’ve been sunk in grief for a long time now. Their anniversary passed with no acknowledgement between he and I, and 65 years swirl, peak and dip like that kite sailing over the topo map of their lives, wanting celebration. Last night I joined him in the dining room. He is so lovely, so awakened in my presence, funny and laughing with his full mouth, eating ice cream and ham together in a quiet, joyful and un-kosher enthusiasm. He keeps thanking me for coming to visit them. His gratitude is beautiful. He has become pure love.

He says, out of the blue— “Mom's been gone a long time, huh?”

I say “Yeah”, so grateful that I don’t have to tell him again.

“How long?”

“A month and a half daddy.” I know to the minute how long she’s been gone.

“Nah. Jeez, it’s been much longer than that!”

“How long do you think?”

“Two or three years at least I think."

“Nope. Just a month and a half.”

“Where is she?”—He is so unbearably innocent and open. And he still doesn’t remember.

“She’s o.k. Daddy. And she loves you so much.”

And then I just stared softly into his eyes for a long time, his eyes that look so much like mine and I said

“She died, Daddy.”

And I brace for impact.

I’d only hesitated from the confession for one heartbeat. It’s like I’d ceased to be able to redirect or to lie—she’s in the shower, at her sisters’, getting her hair done—After the day of sorrow, I have no more strength for this game. Feeling the tears flood me, I still hold his gaze so he can see in our shared eyes how much I love him, how I just am there, right next to him. I take his hand, tears starting to fall down my cheeks.

“She did? Did i know?”

“Yes. But you forgot.”

“How could i forget that?”

“I dunno, Daddy. It's hard to remember things when you get older. And maybe it’s easier to forget than remember.”

“But how did i forget That? Were you with her?”

“Yes, and you were with her too.”

“Did she die in Florida?”

“Nope. She died right here, with us.”

“Did she suffer?”

“Just a little. But she'd been dying for a few years, Daddy."

“Oh, how sad. How did i forget?”

And then he blows my mind—“You were trying to protect me”, he says.

And we both cry together in each others’ arms, there in the residents’ dining room surrounded by now-familiar strangers.

“You know where she's buried, daddy?”

“Jeez, I didn’t even know she was dead. Where’s she buried, honey?”

“On my land. 40 steps from my front door.” I point vaguely west.

“What? A person can do that? That's unbelievable!”

“I know daddy. When you get stronger and the weathers good, I'll take you up to see her.”

He thinks for awhile. Smiles sadly at me.

“Where did you think she was at for 2 or 3 years, Daddy?”

“I don’t know. The hospital?”

“I’m so glad she wasn’t in the hospital. She was right here with us.”

“Can I ask you a question?”

“Sure.”

“Did Lil and I have any other kids?”

Shit. That one takes me down hard.

“I wish you had, Papi, but no. Just me. It's just us now, Papi.”